We hit the ground running. It was September 2008 when we relaunched our business, and although much of the world was in the tumult of the financial crisis, we were on fire. The relaunch had gone stunningly well, even though we had inherited some severe problems from the previous owners. We had debt-ridden relationships with our vendors, an utterly unusable website (which was a big deal for a web-based company), and several hundred frustrated customers who had paid their fees to the previous owners and gotten little if anything in return. But despite all that, we were growing like crazy.

It was hard work, but it was so much fun. We would start the day full of excitement and end the day righteously exhausted. My partner worked the phones and had the sales pouring in while I worked the back end getting the job done and getting our website back online. We immediately brought in a couple of employees who had worked for us in the past, and it was go time.

Over the next 12 months, more and more sales came in (in part thanks to finally having a working website again). So we hired and hired and hired. Like so many startup entrepreneurs, we basically had three criteria for a new employee:

- Did they have a pulse (if I’m honest, sometimes this is the furthest we made it)

- Did we like them?

- Did we think they could figure out how to do the job?

And one day, I suddenly woke up to the fact that someone needed to manage all of these people and that someone was me. It was incredibly frustrating.

At any given time, I was working on three or four projects. But I would find myself working an entire day without touching even one of them.

Instead, I was constantly helping employees out, problem-solving, and smoothing things over with customers. I had work I needed to do, but more and more, it seemed like all I did was fight fires and fill in gaps for other people. I was the “boss,” but if I’m honest, most days, I felt more like I was working for them than them for me.

I started avoiding the office. I would work from home so that I could get something done. I would come in early or come back and work late or over the weekend just to have the time to do what I needed to do without being bothered by someone else.

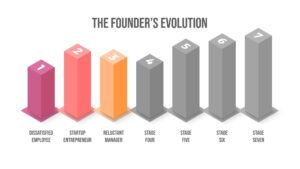

I had reached Stage 3 of my Founder’s Evolution. I had become a Reluctant Manager.

What’s wrong with these people?

Have you ever asked yourself that question?

Or have you’ve thought to yourself, “If I need it done right, I’ll just have to do it myself?”

Or maybe you’ve asked, “Why doesn’t anyone see this the way I do?”

Or perhaps you’ve thought, “I work so much harder than these people.” And if you’ve said it, I can all but guarantee you’ve thought it 1,000 times for every time you’ve let it come out of your mouth.

It’s the defining question for a Reluctant Manager. It’s at this stage that you realize not everyone is wired like you, but you probably haven’t entirely realized yet that that is a good thing. I mean, would you work for yourself?

While all new managers, who are high performers in their own right, feel this same way, there’s an added layer for the Founder. Your people’s pay is coming out of your pocket. And you’re looking at them thinking, “I could have bought a new boat in cash, but instead, I’m paying you to sit there and ask me questions and do a half-baked job to boot.”

It’s infuriating.

Now, I want to pause to say, it’s not that they are doing a lousy job. And as you’ll learn (typically at a later stage), the vast majority of the problem is you, your hiring, your training, and your managing. You’re probably a pretty lousy manager. Again, would you work for you?

And here’s why it matters. And this is what separates stage 3 from stage 2. You can’t do it all on your own anymore. You are now dependent on those you hired to do your job. And, especially at first, that is very uncomfortable.

The Captain on the Field

Being a reluctant manager is like being the captain on the field. You have a job to do just like every other player on the field. You’re likely better at that job (and maybe a few of the others as well) than anybody else on the field.

BUT (and this is a big BUT), you don’t just need to be great at your job. To win, you now have to make sure everyone else is doing great at their job as well. You can’t just throw the ball to yourself for the win. You need (not want, not even get to have), but need to have others executing their jobs well so that you can do your job and your organization can grow.

This has a whole host of unintended consequences. Here are what I believe are the top three.

You have to call the play and then run the play that you called. Your ability to change the play midstream is only as good as your ability to communicate the change to everyone else. Back in stage 2, if you wanted to go left, all you had to do was turn left. But now, if you go left, and everyone else is still going right, you either fail or have to work at least twice as hard to succeed.

You are on someone else’s schedule. Most of the people you hire are going to work mostly normal hours. They are more likely to be there at 2 pm than at 2 am. That means if you need them, or even worse if they need you, you need to be there at 2 pm with them while they are working. This is a taste of prison for many founders and one that we resent if we’re not careful.

You have to hold others accountable. If you’re like founders, you probably don’t want someone else telling you what to do, looking over your shoulder while doing it, and reviewing your work when it’s done. That sounds terrible, right? Yet, that’s what you need to do if you want to make sure everyone else is doing what they are supposed to be doing. Not all the time, but a lot more than you probably do. At this stage, you don’t just get to say jump, and everyone knows exactly where to jump, how high, and how many times. You have to teach, train, monitor, and review, and you probably aren’t too fond of any of that.

So what do you do?

The essential strategy for Stage 3

Being a reluctant manager is, quite honestly, quite miserable. But it’s also entirely avoidable. To find your way through, you have a decision to make.

- Make your decision: The decision is this, do you want to move forward or backward. And before you jump to the conclusion that forward is always better, consider what it is you actually want. Do you want to be the star player? Do you want to stay in the game? Do you want to do whatever it is you want to do, unencumbered by others? If so, then you’ll want to find a way to simplify, lessen your headcount, and go back to Stage 2. If that’s not enough. If you’re going to build something bigger, something better, then you need to stop resenting your role as a manager and start embracing it. Your success will be defined more and more and more by your ability to manage well. So much so the next stage stays on the sidelines, but I’m getting ahead of myself.

- Speak and think in terms of the team’s success: You have to take a look at the pronouns you are using. How often are you saying “I” and “you” versus “we” and “us?” This seems simple. Trivial even. But it’s groundbreaking. Right now, you and the organization are likely synonymous. When the organization makes a profit (or grows its impact), you make money. When you want to go in a direction, that becomes the vision of the organization. You need to double down on your use of plural pronouns. “This is our goal for the year.” “We will succeed when we….” And even “When you drop the ball here, this is how it affects all of us.”

- Find your #2: I could write an entire book on this one topic; it’s that important and impactful. You only split so many ways. You can only manage so many active connections in your mind. You don’t scale. Once you get to 10 or more staff, you’ll likely find working in the organization and trying to grow it simultaneously is dizzying, if not downright impossible. You will enjoy stage 3 far more, you will accomplish far more, and you’ll do it all in far less time if you can offload some material part of the organization to someone else who you trust.

Transitioning Out of Stage 3

You can achieve substantial growth both personally and organizationally in stage 3. And in doing so, a curious thing happens. Where you once were the only one who could do the job right, you’re now the most likely one to be messing things up.

There are new systems and processes, and there are people who spend all day every day doing what you did at most for 20 minutes a day, even when you were a solo operation.

You’ll have star players that can catch the ball better than you, run faster than you, and do their one thing better than you, whatever it is.

And this creates a conundrum. What do you do? You used to win by being the best, selling the most, and being most loved by your customers. Now some customers don’t even know your name.

It used to be when you were gone, nothing happened. But now, if you leave for a week, it seems like the team is more productive than when you are there.

It can feel like you’re being put out to pasture.

This is the fourth stage in your Founder’s evolution: The Disillusioned Leader. And I think it is the most challenging stage of all.

Enjoy the gift of Stage 3

Because stage 4 is so hard, it is even more critical to find a way to thoroughly enjoy Stage 3. Don’t waste time resenting the people who work for you and the needs they have along the way. Don’t lament having to get in and get your fingers dirty. Don’t worry about the mud on your boots. Enjoy it.

Enjoy that you still get to do the work. Enjoy that you have others who can do more and more of the things you don’t like to do, even if they do it differently from you, even if they mess it up from time to time. These are good days. You will likely build some of your deepest, most fulfilling working relationships during this time. You will likely enjoy more freedom of choice during this time. You will likely achieve the highest impact in the shortest time from decision to execution. So don’t let the challenges of Stage 3 steal all the fun that you can truly enjoy during this stage in your journey.

[yotuwp type=”playlist” id=”PLNTSkWehajGNtj6LhdqsMg0ekVfRm1p4m” ]

The Founder’s Evolution Stage 2: The Startup Entrepreneur

The Founder’s Evolution Stage 2: The Startup Entrepreneur